The Flight

The aircraft flew a cross Channel trip in the early morning, landed at Southend and took on a fresh crew who had been on standby and not expecting to fly that day. The Captain was not with his usual first officer and instead flew with a relative newcomer to the airline but someone, who as we have already seen, had great experience at flying transport and passenger aircraft.

Zulu Bravo took off again at 9.37 am, on the outward trip from Southend, heading

for Portsmouth and after that the Channel Islands. This was an additional relief

flight to retrieve fog bound holiday makers -

Unfortunately this failed attempt may have set in train the events which followed.

It was clear that the weather was far too bad to attempt a standard let down and

that the only way in for a large aircraft like the Dakota would be to go 'under'

the weather on the last stages of the flight. Without radio, the assessment of the

conditions and ' runway visual range' -

Alarming very low level approaches to Portsmouth were not unheard of, so what was proposed was not particularly unusual. Today all Hell would be let loose when the authorities came to hear of it, but on occasions Channel planes actually damaged sailing yacht masts of boats moored in the approaches, so scraping in under the weather was par for the course. They really did have to come in that low on foggy days so as not to lose sight of the ground. And today being a Sunday, there was no Ground Control Approach Radar to help as the RAF station at Thorney Island didn’t operate on Sunday.

After loading passengers and freight in Guernsey, the plane flew to Jersey landing at 12.25pm. There was another Channel Aircraft, a DH Dove, parked on the ramp, flown by the chief pilot of the airline. This was also scheduled for Portsmouth and was the one intended for the original flight, Zulu Bravo being sent to carry the passengers that were now overbooked on that trip due to the bad weather. More passengers boarded and a quantity of fresh flowers were put aboard as freight. However some passengers seemed to have had last minute changes of plan including one who decided at the last minute to return by sea with the family car, leaving his wife and two infants on the plane as it would be a faster and smoother journey.

As all passengers were booked to Portsmouth there was a strong commercial incentive for both planes to reach the airfield, although diversions were given as Southend and Stanstead if it was impossible to get in to the grass airstrip. The crew discussed the weather with the met officer at the airport and then it seems that things began to fall apart.

Both aircraft were scheduled to fly on to Southend after Portsmouth but ZB’s flight crew were running out of flying hours and would soon have to take an overnight break. However the Chief Pilot seems to have pulled rank and insisted that his plane, a DH Dove, smaller and lighter, departed first for Portsmouth as it was the original plane and needed to keep to the schedule. If this happened, ZB would arrive later and have to wait as the airfield could only handle one aircraft at a time. This would run ZB’s crew out of hours and they would have to stay in Portsmouth overnight and fly home in the morning.

The Dove was scheduled for Paris after Portsmouth which presented a problem for the

stewardess aboard as she was getting married ( in Paris ) in a few days time but

needed to return home to Southend to finalise arrangements. Her colleague on the

Dakota was happy to stay away overnight and pick up some overtime pay -

Back in the terminal building a furious argument now took place between the Captains and senior airline staff. There is no record of exactly who was involved and in what capacity but several witnesses heard what was a most unusual occurrence prior to a passenger flight. Channel was still operating under the old aegis of RAF ‘discipline’ and a standing order was that in bad weather crews must attempt one landing before they could divert. Under normal circumstances this was a sensible way to reduce passenger inconvenience and financial loss, but it did rather imply that senior management didn’t trust their pilots and Channel’s accepted weather minima were far below any other operator as was stated in the accident report’s findings.

Jersey Airport in 1961 -

Knowing the conditions and without being able to speak to the airfield by radio to see if visibility had improved, the only ‘safe’ way to approach was to let down over the sea, where there are no obstructions, pick up the coast line and fly at low level across the Solent, then make a visual approach 'under the weather' to the airfield. The weather forecast implied that this would be just possible.

Channel operated in much lower visibility than the other regional airlines, but the crew were experienced and the Dakota had good performance. Portsmouth runway was effectively at sea level and by keeping in sight of the ground or sea at all times, although spatial disorientation over the sea is a serious risk, the landing could be achieved safely.

However once in fog or cloud, which that day was virtually at ground level, there

were no visual reference points, no radar direction nor any instrument landing system

or communication with the airfield. There was just one imprecise radio aid that

gave an approximate heading to the nearest beacon. They were on their own, flying

blind and travelling at 150 miles per hour. Once they lost sight of the ground there

was no way to safely re-

Thus with huge, if unofficial and in modern parlance ‘deniable’ pressure on him to make an approach to an airfield he had already unsuccessfully attempted, with the potential of inconveniencing passengers who had been delayed already, running low on flying hours, no runway approach aids, and an airline that accepted flying on the limit of prudence as acceptable, ZB’s captain perhaps chose the only way he believed he could make a safe landing at Portsmouth.

The original flight plan was abandoned -

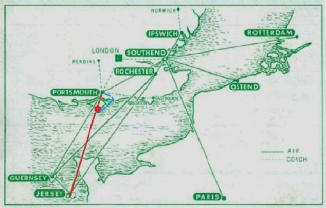

From the 1962 timetable. This map shows the original track in red, with the approximate crash site marked, and what we believe to have been the proposed route to fly under the weather, shown in blue. The critical point was to pick up the coast of the Isle of Wight where visibility was expected to be about half a mile at low level. That's not far when travelling at 150 miles per hour!

Leaving Jersey with up to the minute weather reports, and following the Dove, ZB and her much delayed passengers began the return flight at 1.54 pm in good weather.

After climbing to 3000 feet the crew reported they had Alderney in sight at 14.07.

They reported again in mid Channel -

A radio message at 2.15 pm as the plane passed Alderney, requested permission from London Air Traffic Control to come down to 1000 feet and the crew were careful to check and confirm the barometric pressure to ensure that their altimeters were set correctly, thus they were clearly aware of the need for accurate navigation and height on the next leg of the trip. Still over the sea the aircraft flew on, descending steadily and presumably intending to make landfall on the Southern tip of the Isle of Wight and then follow the coast where the weather forecast implied that they would be able to see the cliffs in good time.

Unfortunately it seems that a combination of factors now added to the ‘pyramid’,

each one on its own being little more than an irritating -

The aircraft had one radio navigation aid -

Although the flight crew would have been flying on instruments in the cloud as the plane descended, one of them would have been watching intently for the coast to appear as they broke through the forecast cloud base between 600 and 1000 feet. Tragically the location where the plane now reached the coast was perhaps the one spot where a blind valley above the town of Ventnor mimicked the coastline in appearance and direction at the point of intended landfall just a few miles further along. A matter of yards either way and it is doubtful if the accident would have happened. The crew may have had a severe fright but would have been high enough to miss the ground!

Unfortunately the cloud was much lower than expected and we believe that the plane was still in zero visibility when it crossed the coast. The local coastguard at St Catherine's Point recorded almost zero visibility and so did shipping near the coast. If the crew did glimpse the Isle of Wight, they may have mistaken the Western ( right hand side as you look at it in the picture below ) side of Coombe Bottom (left photo) for the cliffs at Bonchurch a few miles further East. ( Right photo). More likely is that they never even realised they had crossed the coast.

About one minute's flying time along the coast the hills are much lower with a rolling

landscape -

When they did see the ground there would have been no immediate indication of a problem

as it would have appeared at the correct angle to the track of the plane. As the

other side of the valley was lost in the cloud, the crew may have seen what they

expected to, assumed they were still over the sea and turned slightly to fly along

the 'coast' and across Sandown Bay -

At 2.28 pm the local coastguard heard, but could not see, a low flying plane, and

a few seconds later a taxi driver waiting at Ventnor station was startled as a huge

aircraft roared over the roof of the building. In Ventnor, television screens flickered

as the huge aircraft disrupted the signal. Off the Needles the crew of the Trinity

House vessel 'Siren' heard a low flying aircraft -

The plane was already in a steady climbing turn to starboard ( right ) although this seems to have been a planned manoeuvre and not an evasion, and it seems likely that the descent was already being aborted . There was no warning of what lay ahead and the passengers were reading or looking out at the blanket of cloud surrounding the plane. Suddenly the engines went to maximum power, the plane banked steeply and the nose came up sharply as a hillside loomed out of the fog. It was only a matter of seconds, and just too late. One of the survivors reported that the crew gave the engines full power ; “ I was reading the paper when he banged on the power and started to turn” . The way this was done indicated that the plane was in trouble. Despite full throttle the plane just would not climb fast enough to get clear.

Climbing is a factor of height gained, engine power and speed -

Realizing they were going in, the Captain flung the plane into an opposite bank, levelling the wings and at the last moment raising the nose to create an initial glancing impact; his final action was to close the throttles, indicating that his thoughts were now to mitigate the impact. It was this final manoeuvre, with huge presence of mind and skill, that saved some of his passengers.

At 2.29 pm GMT the radar trace from ZB showing on the Siren's display vanished into the returns from the island. The operator waited for it to reappear. It never did.

Flying on a bearing of 050 degrees true Channel Airways Dakota G-

The aircraft hit rising ground just outside the radar station compound, bounced violently over the fence, the tail tearing through two sections of the chain link fence and flattening the posts. The aircraft missed the concrete bases of one of the old radar towers, and slammed onto the ground in the centre of the compound before careering across the gorse and heather, striking the old radar receiver building and skidding another 100 yards until it came to rest straddling the access road through the site on the very highest point of St Boniface Down.

However it did not cartwheel or break up and the controlled and level way in which it hit the hill gave some the chance of survival by reducing the initial deceleration and allowing the inertia to be absorbed progressively and not in one shattering impact.

A typical Channel Airways scene -

The aircraft left an impact crater that is still visible under the vegetation, and the track over the ground is even visible on Google Earth as there is a change in vegetation along the path taken by the wreckage and the ground is still poisoned by the fire at the final resting place of the wreck half a century later.

Conditions were so bad that a party of Civil Defence volunteers exercising just 250 yards from the crash were unaware that it had happened and it was left to a local man, Ted Price who had been picking bean sticks on the hillside, to demonstrate incredible bravery by entering the burning wreck seven times and rescuing seven survivors until driven back by the exploding fuel tanks and tyres.

The emergency services swung into operation, alerted by a blind radio enthusiast on the Island and members of Northampton Radio Club who were operating on the Down that day. They not only alerted the authorities via another amateur on the mainland but provided rescue facilities and emergency communications until the Police were able to get a radio car to the site.

Staff at Ventnor Station also heard the accident and dialled 999. Emergency services were on the scene in just a few minutes and within a quarter of an hour the survivors were on their way to hospital, an extremely rapid response given the conditions and location of the accident at the top of a 1 in 2, single track road. Following their departure it was left to the Police and Fire Brigade to damp down the remains and secure the area.

Around tea time the mist and fog lifted to reveal a lovely sunny evening. It was too late.

Known as a meticulous pilot, ZB’s Captain had tried Portsmouth earlier and decided it wasn't safe to land. Although he knew the route well, he was not familiar with the awkward let down with no navigational aids, where planes turned onto final approach to the grass field when they passed a large neon sign on the Phillips electronics factory !

He had just proved beyond reasonable doubt that a traditional approach to Portsmouth was out of the question, yet less than an hour later he was expected, perhaps instructed, to follow the ‘rules’ and make a further attempt at something he considered unsafe in a Dakota. Added to the issue of which aircraft should leave first, the ‘pyramid of circumstances’ was building.

In an attempt to defuse the situation, the Chief Pilot, something of a gentleman and flying the scheduled DH Dove, which was providing the original service to Portsmouth ( ZB was handling the overflow and freight ) offered to toss for first departure. A coin was produced, and ZB’s Captain lost. Sadly this action was later claimed by some journalists to imply that the two aircraft crews were ‘racing’ and was done to provide a fair start. This story did much to tarnish the reputation of both crews and was completely and utterly untrue, although it made for sensational headlines at the time.

On the ramp everyone was settling in for the flight unaware of the issues in the flight office. After a brief conversation with the flight deck, the two stewardesses grabbed their flight bags, sprinted across the tarmac and exchanged places, doors closed and both planes started engines. In such moments lives are changed.

On Zulu Bravo, the Captain, passed a message to the passengers, via the breathless Stewardess, telling them that he would 'do his best' to get them to Portsmouth. He was still incandescent at the treatment shown to him and clearly very concerned about approaching a fog bound airfield with which he was not over familiar. Perhaps he felt there was no choice and that he had to go.

The aircraft flew directly in from the sea up 'Coombe Bottom', over Ventnor Railway Station, in a gentle arc towards the camera, striking the ground below the fence, demolishing it and coming to rest some 250 yards behind and to the left of the photographer.

The aftermath -

The aircraft scheduled for the original flight was a DH Dove -

| Instruments |

| Visibility |

| Navigation |

| An Alternative Theory |

| Pressure On Crews |

| Blame |