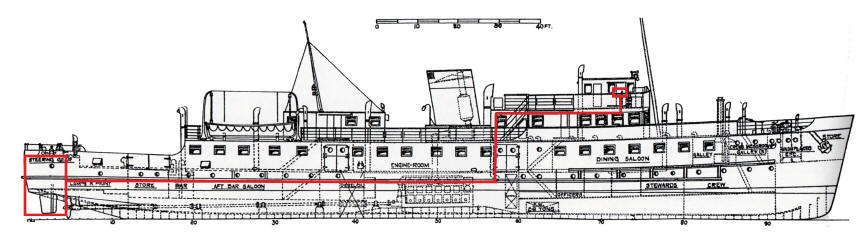

STEERING

Ships are steered by rudders. These are moving plates at the back of

the ship that twist. These work in two ways, firstly by pushing the

water flowing away from the propeller away at an angle and secondly by

deflecting the water as it moves past the ship. This puts a force on

the rudder which acts on the bearings that hold it in place ( the pintle )

and this pushes the back of the ship sideways. The ship is long and

thin and this force acting on the back causes the ship to turn in the

direction of the rudder. However the front ( bow ) does not move

sideways very much - in fact the back ( stern ) of the ship swings out away

from the direction of turn and the ship then pivots about a point generally

about one third of the way along the length. This has the effect of

throwing the stern towards an obstruction before the ship starts to turn

away from it ( That is what did for the Titanic ! )

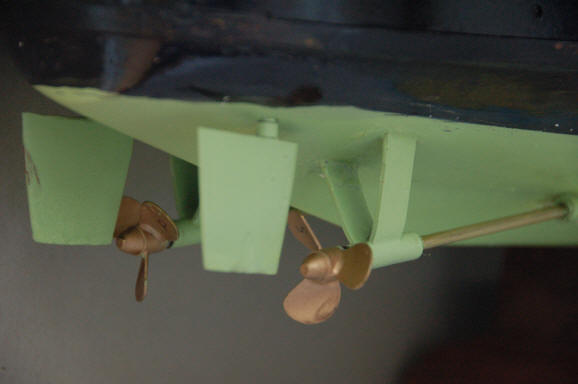

These are twin rudders and propellers on a scale

model. You can see rudders and the pintle where they enter the hull,

the propellers, the A brackets, tail shafts and stern glands. On this

ship the propellers are 'handed' so that they each turn a different way.

This makes the ship more directionally stable as any twisting effect from

the propellers are cancelled out. The real Balmoral has four bladed props !

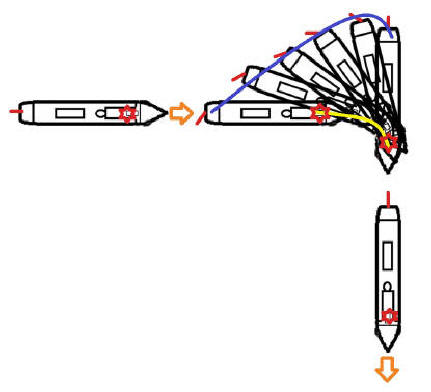

HOW A RUDDER TURNS A SHIP.

In this diagram, the rudder is in red and the fulcrum or pivot point about

which the ship turns is the red star. The yellow lines shows the path

of the front of the ship and the blue line shows how the back takes a much

wider path which tends to tighten as the turn progresses. The ship turns

about a point about one third of the way along the hull. This diagram is

wildly exaggerated to show what happens!

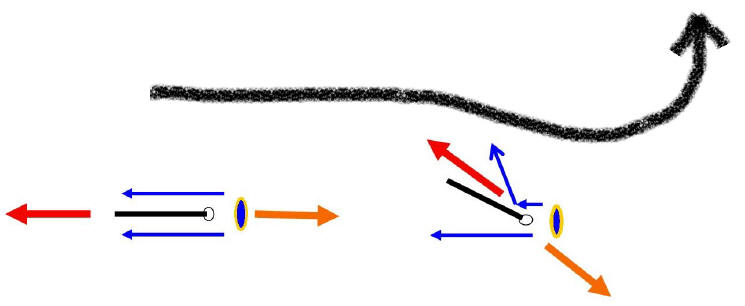

FORCES ON A RUDDER

This is an attempt to show the forces acting on a rudder ! The propeller is

the blue disc with a yellow edge, the blue arrows show the water direction,

the red arrow shows the resulting thrust ( pushing force ) generated by the

propeller and rudder, and the orange arrow shows the direction in which the

back of the boat will try to go. The black arrow shows the path of the ship

through the water.

In the left hand diagram, the rudder is straight ahead and the

propeller wash and thrust are both going in a straight line. The ship moves

straight ahead.

In the right hand diagram, the rudder is turned to the left and is

deflecting some of the water from the propeller to the left. This puts

a sideways force on the rudder as the water changes direction when it

strikes the rudder and reacts

by pushing it the opposite way. This force which is

trying to push the rudder straight acts at an angle giving a turning

force which is transmitted through the rudder pintle to the back of the

ship. However there is still water flowing directly away in a straight

line behind the ship, so the turning effect is a combination of the sideways

force acting on the rudder and that pushing the ship along.

Because the rudder is at the back of the ship, the effect is to push the

back, away from the direction in which the rudder is turned, and because the

boat then pivots about a point towards the front, this causes it to turn in

the direction the rudder is pointing.

There are additional ways to steer ships. Some have bow rudders to

help push the front round, there are bow thrusters, ducted

propellers that push water through a tube across the inside of the

hull to move the front sideways , and it is possible to alter or reverse

one of the engines ( if the ship has more than one ) to help pull the bow

round. Most ships with two propellers will have two rudders, as a

rudder in the wash from the propeller will have far more effect than

one which relies on water passing it from the forward movement of the hull.

This is also a problem when trying to go backwards ( astern ). There

is no speed of water over the rudder and no propeller wash to help as

the water is flowing the wrong way ! Many ships have great difficulty

going astern, particularly at low speed and in some cases if there is only

one propeller and it is a big one, the turning effect of the screw can push the stern in

one direction regardless of which way the rudder points !

Rudders are big and heavy to be able to handle the forces applied to

them, a large ship like Balmoral needs steering gear. On early ships this

was a wooden rod ( tiller ) mounted on the top of the rudder shaft ( stock )

but this was difficult to control , especially in a rough sea, so a steering

wheel was introduced with ropes to link it to the tiller. This reduced

the effort needed to turn the rudder but required a lot more turns of the

wheel, and on sailing ships it could sometimes take several men to

hold the steering steady. As ships developed and used engines, the steering

position moved from directly above the rubber where ropes could be used to

move it, to a

position near the front. This required a linkage to take the movement

from the steering wheel right along the ship to the rudder and ropes didn't work as they were too

flexible. The force needed to

turn a large rudder was huge and only massive chains and shafts could transmit

the load - this wasn't practical, so someone had to invent the powered

steering gear system so that the person steering (helmsman)

could turn the wheel easily, there would be small linkages running the

length of the ship and a big powerful machine above the rudder to transmit

the movements from the input shaft to the steering. Originally this was

steam powered but modern ships, including Balmoral use a hydraulic system

driven by an electric motor.

STEERING GEAR

On Balmoral, the steering wheel is on the bridge in the wheel house.

It is connected by gears to a series of shafts that run down from the

bridge, through ceiling of the observation saloon and then into the engine

room. The shafts then continue along the side of the ship to the 'steering flat'.

This the area under the rear poop deck which houses the top of the rudder

stocks and the steering engine. This is a large hydraulically powered

pump that does the same job as a power steering system on a car. It

takes the control input from the steering shaft and applies it with much greater

force to the rudders. In this case as there are two rudders they are

linked with a rod so that they both move together.

The steering wheel is on the bridge and turns a series of shafts that run

through the ship .................

The input shaft from the steering wheel on the bridge is marked with red and

white tape , here the shaft is coming down from the deck house into the

engine room, through the red gearbox and out towards the side of the

ship to clear the engines ......

..... then it runs right along the inside of the hull and reaches the

steering flat where it has more gearboxes to bring the shaft back into

the middle of the ship, then it enters the red gearbox before going

aft..........

to the steering engine................

which amplifies the force from the man on the wheel and operates a hydraulic

ram that is connected to the rudders................

You can see the Port side tiller arm, the linking rod and part of the

control system painted red.....

........ and that system changes the direction of the rudders and controls

the ship. The propeller wash is deflected by the rudders and this greatly

improves the steering by pushing the water to one side. This is a photograph

of Balmoral in dry dock and you can see the propellers and rudders.

EMERGENCY STEERING

If the steering system fails, there is a small emergency steering wheel on

the poop deck and this can be connected to the rudder. The main

steering engine can then be disconnected from the final linkage and the ship

can be steered by hand. Its a hard job but better than having no

directional control at all!

Here is the emergency steering wheel and part of the emergency steering

system in the steering flat. The man at the wheel would be unable to

see where the ship was going but would be told how to steer by a chain of

people passing orders from the bridge - or he might be given a portable

walkie talkie radio !

In the event of steering failure it might be possible to steer the ship by

using the two engines at different power settings or even running one

backwards.

This is sometimes done to help manoeuvring and is known as 'splitting the

sticks' as the engine telegraph handles point in opposite directions.

It is not a good method of steering as the rudders have a very powerful

effect and unless they are dead straight they would have a huge effect on

the steering.

Emergency steering wheel.

Emergency linkage.

Emergency gearbox and steering rod.

In the right hand photograph, the bar with the red

clip ( clevis ) on top of the gearbox is the part that is connected to the

tiller arm on the right of the photograph when the emergency steering

is needed.

All this is contained under the poop deck at the very back of the ship.

HOME