Ships use ropes to

hold themselves against a pier and dock walls. The

ropes are secured to bollards , steel posts with a wide top bolted or

concreted into the structure of the mooring. These

have to be extremely strong as they not only have to hold the ship steady but

have to keep it in place when the wind is blowing or if there is a strong

current. The ropes also have to stop the ship moving when it arrives and there

can be a huge force exerted as the inertia of the ship - this is its weight

multiplied by the speed it is travelling - this force must be taken up by the

rope and the mooring bollard.

When the 'haul in' signal is given on the

docking telegraph ( see the section below for

details about this signalling system ) the operator pulls on the slack end of

the rope that is wound loosely round the drum of the winch. This tightens the rope slightly on the drum

and it grips the surface. The amount of tension on the free end of the

rope is multiplied several hundred times and the resulting force is enough to

move the entire ship, pulling it into the correct position. The Captain signals

with the docking telegraph or a hand held radio to tell the winch operator what to do and by heaving

in and paying out the ropes at each end of the ship, she can be positioned in

exactly the right place regardless of the wind and waves. If the ship is to be

moored for any length of time or in bad weather, additional ropes are run ashore

to provide additional security.

A skilled crewman can use just a light tension on the

free end of the rope to exert a huge force - so much so that it can

even break the rope!

You will see that below the hawsehole

where the rope enters the ship which is the rounded hole in the side

through which the ropes leave the ship, is an anchor. Unlike a car or bus,

a ship has no parking brake and will only stop if it runs aground or is moored to a

solid object ! To stop at sea, it is necessary to lower an anchor. This

is sometimes called 'Dropping the pick' or 'Throwing out the Hook'. The anchor is heavy

steel weight with prongs ( called flutes ) on a very long chain. It falls to the sea

bed and is weighted down by the chain so that it falls onto its side and the flutes dig

into the sea bed and prevent it moving. The ship then pays out a long

length of chain so that the weight keeps the anchor almost flat on the bottom,

and this holds the ship in one place. She will actually swing round the

anchor as the tide and wind affect her and must be well clear of any

obstructions or other ships, but in very simple terms, the anchor is lowered and

the ship can then stop. The anchor holds the chain in position but the

heavy chain holds the ship.

It is easy to lower the anchor, but very difficult

to get it up as you have to pull all the chain up first and even Balmoral's

anchors which are quite small, weigh around 400 kgs each and the chain much more

than that. This is also a

job for the winch. The rope drums can be disconnected and the chain

lifters driven by the winch motor. These have 'snugs' into which the links

of the chain fit so that it grips and the free end of the chain is fed into a

chain locker below the deck.

There is an anchor on

each side of the bow. When the anchor is dropped it is 'let go' and falls

under its own weight. This makes a tremendous noise as it falls, a huge

splash and then it slows up as it lands on the sea bed. Once the chain

speed has slowed down, the anchor is allowed some more chain to 'set' in

position and then the ship may be reversed very gently to make sure the anchor

is holding. The two 'T' handles beside the motor operate a brake band to lock

the winch mechanism and when at sea the chain is locked in place using 'bits' and

in this photograph, also a steel cable .

A major problem for

ships is if the anchor is 'fouled' and catches on an obstruction or cable. As

you can't see the bottom there is no way of knowing what is down there.

The chart will show the type of bottom, rock, mud, sand etc but not the exact

conditions at a particular point.

In some cases the winch can't pull the anchor up if it is trapped by wreckage or

a rock and this might endanger the

ship, so the chain has to have a line tied to it and is then cut. Anchors

are expensive, so it is usually necessary to hire a diver to go down and free

the anchor and then retrieve it later. All this takes a lot of time and

money and also a reason why the ship has two anchors - in case one is lost !

Balmoral has lost several anchors at Lundy Island over the years but they have

all been recovered by diving enthusiasts who attach a rope and float to the

chain so that it can be picked up and pulled aboard the ship. However

cutting the cable is the last resort and only done after a major fuss trying to

free the anchor by moving the ship about and pulling very hard with the winch !

Even worse is if the anchor happens to land on a telecoms cable or power line.

These should be protected and are all well marked on marine charts but it does

happen and occasionally causes havoc by cutting power or communication to

islands and remote areas - and a very big bill for the ships owners !

At the stern of the ship is a smaller capstan type

winch with a vertical drum. This is only used for rope handling and does not

have a facility for handling chain, although there is a small anchor stored on

the rear ( poop ) deck for use in an emergency. The photograph below was taken in

1975 before Balmoral had her car deck enclosed - at this time she was still

registered in Southampton. You can see the capstan drum and winch motor

and two members of the P & A Campbell crew together with the hawseholes and

fairleads used for running out cables.

DOCKING

TELEGRAPHS

.JPG)

.JPG)

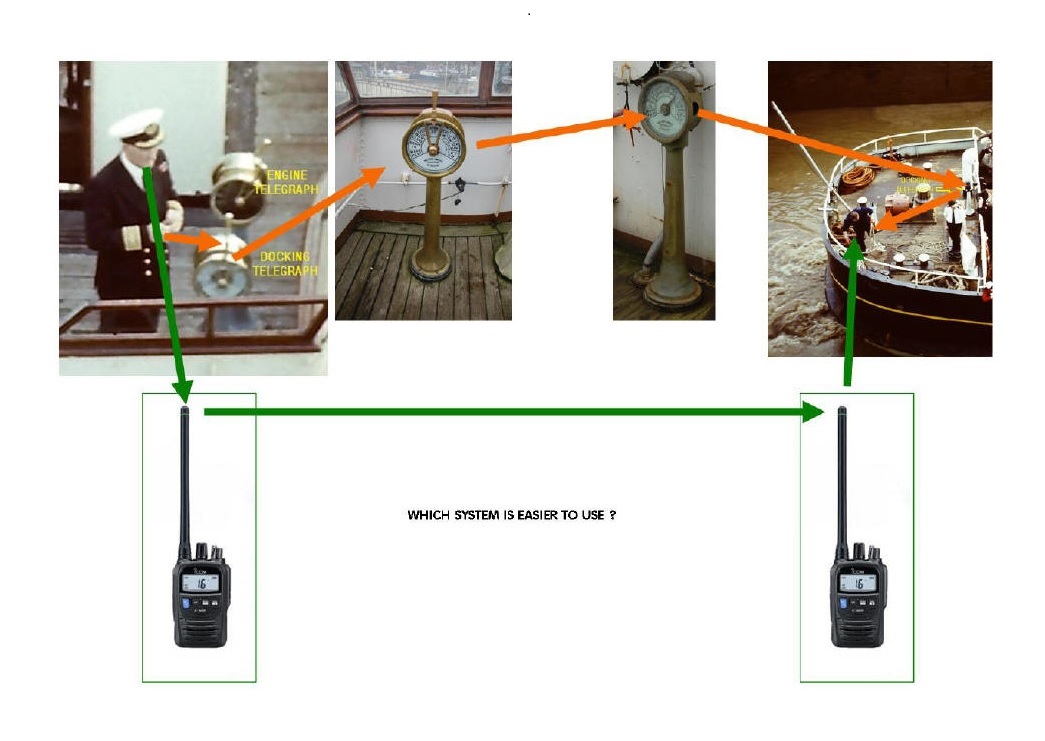

Before the days of hand held radios, it was necessary for the crew

working the mooring ropes to be told what to do, and when to do it. The ropes have to be tightened and released as necessary to

manoeuvre the

ship alongside a wall or jetty or to help turn her round in a confined

harbour. This can be a tricky operation and it is vital to get

the ship in exactly the right place - otherwise the gangways won't fit the

space made for them on the pier head and passengers can't get on or off!

In the Bristol Channel with fast tides and strong currents this can be a

skilled operation. Moving a 600 ton ship in a fast tide with a wind blowing

takes a lot of power- and that has to be controlled accurately. The engines

can do some of the work, but the final job of securing the ship in the right

place and holding her there against wind, waves and current is the job of

the ropes.

.jpg)

As you can see from the

photographs, the Captain can't see the stern

of the ship where the mooring lines are handled and

certainly can't shout that far, but he has to be able to tell the

crew there what to do. The ship is equipped with a set of 'docking

telegraphs' similar to the engine room telegraph but without the

reply facility so that the men on the deck at each end of the ship can

moor the ship in the right place. Thiss is the

purpose of the second telegraph binnacle on the bridge.

There is no way for the crew to tell the bridge of something is wrong and

the directions only go one way. Thus if a rope breaks or gets jammed,

the Captain won't know unless someone runs the length of the ship to tell

him. This was how commands were passed before cheap and lightweight

hand held radios. The system was all mechanical relying on chains,

wires and linkages. It was reliable and as soon as the captain gave a

command it was seen by the men on the ropes, but there was no way they could

respond. Using a hand held radio allows a two way flow of information

and a much faster and more accurate result.

These days the docking telegraphs are not installed but are fully restored

and will eventually be put back in their rightful place. However

handheld radios make the job easier and faster.